Stocks Look Good Now, and Would Look Even Better If Lower

The stock market has been, well, interesting, lately. The Dow is down 500, now up 500, now down again. This is nothing compared to past gyrations, including the 20%+ drop on October 19, 1987, but, still, it makes one wonder why stock prices gyrate like this.

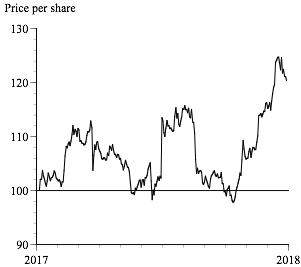

The stock market is made up of individual stocks that typically yo-yo even more wildly than the overall market averages. The figure below shows the daily price of Nike in 2017, scaled to equal 100 at the beginning of the year. Nike finished 2017 up 20%, but there were several 10% ups and downs along the way. Surely, the value of the company didn’t change that much day to day, but the stock price did.

It is not just Nike in 2017. Since October 1, 1928, when the Dow expanded from 20 to 30 stocks, there have been nearly 7,000 occasions when a Dow stock went up or down more than 5% in a single day, and nearly 1,000 days when a Dow stock went up or down by more than 10%. And these are the big, established blue chips.

Long ago, John Maynard Keynes, who was a successful investor as well as economist, observed that the “day-to-day fluctuations in the profits of existing investments, which are obviously of an ephemeral and nonsignificant character, tend to have an altogether excessive, and even absurd, influence on the [stock] market.”

The stock market is like a roller coaster ride—sometimes exhilarating and sometimes nauseating—because too many investors try to time the market, thinking that they can buy before stock prices zig and sell before they zag. They buy or sell based on feelings about whether prices are about to go up or down. Such feelings are easily influenced by fear, greed, and other emotions that Keynes called “animal spirits.” A stock, like Nike, might rise 20% in a few days if enough people get excited about the price rising, and fall 20% in a few days if people get worried about the price falling. Price fluctuations are caused by people trying to anticipate price fluctuations.

It isn’t this way for investments like private companies and commercial real estate where there is no liquid market with constantly changing prices. Because prices cannot fluctuate wildly, investors do not try to predict price fluctuations.

An investor who is considering buying a private company will look at the company’s books—the assets and liabilities, and the income and expenses. Unless the company is going to be liquidated, the most important factors are various measures of the company’s profitability, how much cash it generates. A savvy investor will negotiate a price based on a valuation of this projected cash flow.

The amount that an informed investor is willing to pay to buy the company does not depend at all on guesses about what the price of the company will be a few minutes, days, or weeks later, because there is no market in which the company’s price changes every few seconds, or fractions of a second. It would be a waste of time to speculate about short-term price pirouettes, so investors focus on what really matters—how much cash the company generates.

Not so with publicly traded stocks. There is a stock market with ever-changing prices, and it is tempting to buy and sell stocks based on guesses about which direction stock prices will go next. Many investors succumb to this temptation. Buy Nike because the price is about to go up. Sell Nike because the price is about to go down.

This is a fool’s game because it is not possible to make consistently accurate predictions of oscillations in stock prices. Think about it. At the current market price, there is a balance between buyers and sellers, between investors predicting the price is about to go up and investors anticipating that the price is about to go down. Both sides are confident that they are correct, because everyone thinks that they are above-average investors. Half must be wrong.

Value investors don’t try to predict zigs and zags in stock prices, but they can take advantage of irrational fluctuations in prices. Sometimes Wall Street is having a sale. Other times, fools will pay foolish prices. Volatility is a value investor’s best friend.

Value investors think of a company as a company, not as a stock, and consider whether they would like to be part owners, just as if it were a private company with no publicly traded stock. It can be helpful to pretend that there is no stock market, or that the market will be closed for twenty years. Don’t buy a stock because you think you can sell it at a higher price to a bigger fool. Do buy a stock because the company creates a generous cash flow that you would be happy to receive for decades.

It is admittedly difficult to pretend that there is no stock market, or to consider buying or selling a stock without looking at past prices or thinking about where prices might go in the future. Here, in February 2018, some people see that prices are much higher than in the past and conclude that it must be a bubble. Others look at recent weaknesses in stock prices and conclude that prices will rebound. These are natural, human reactions, but they are not helpful.

Instead, pretend that the stock you are considering buying is not a stock but a company that you will own for the foreseeable future because it cannot be sold for 20 years. Would you rather buy the company or buy Treasury bonds or something else?

It’s your decision, but it should be based on the prospective cash generated by your investment, not on guesses about short-term price movements. One very simple rule of thumb is that the annual rate of return from stocks is approximately equal to the dividend yield plus the rate of growth of dividends. A reasonable assumption for the future long-run growth of dividends is the historical 5% average growth rate.

In March 2000, near the peak of the dot-com bubble, the S&P 500 dividend yield was 1.2 percent. Adding in a 5 percent dividend growth rate, the predicted total return is 6.2 percent:

R = 1.2% + 5% = 6.2%

This was lower than the 6.3 percent return on ten-year Treasury bonds, indicating that stocks were not an attractive long-term investment.

In December 2008, in contrast, the S&P 500 dividend yield was 3.2 percent, and a 5 percent dividend growth rate gives an 8.2 predicted total return:

R = 3.2% + 5% = 8.2%

This was 5.8 percentage points above the 2.4 percent return on ten-year Treasury bonds, indicating that stocks were an attractive long-term investment.

Today, the S&P 500 dividend yield is 1.9 percent, and a 5 percent long-run growth rate gives a 6.9% predicted total return:

R = 1.9% + 5% = 6.9%

This is 4.1 percentage points above the 2.8 percent return on ten-year Treasury bonds.

We are far from either the March 2000 or December 2008 extremes. It is not a bubble and it not a buying opportunity of a lifetime. However, there are currently many attractively priced stocks with strong earnings and substantial dividends when compared to the alternative of buying long-term Treasury bonds paying 2.8%.

I’m not saying this because I want to pump up stock prices. My family’s income is larger than our expenses, so we have a steady stream of money to invest. We are not selling investments to pay our bills; we are making investments to provide for our future and the future of our children.

We are actually better off financially if stock prices drop. A fall in stock prices doesn’t directly affect the cash flow from the stocks we already own. A market crash might have negative effects on the economy and corporate profits, but our stocks are relatively recession resistant, and I am confident that the Fed will keep any recession from getting out of hand. The companies we own will keep making profits and paying dividends.

On the other hand, a decline in stock prices will allow us to buy additional stock at lower prices. I would rather buy Apple at $160 or $140 than at $180 or $200. Lower stock prices are positive, not negative, for my family. Perhaps they are for you, too

I like stocks at current prices and I would like them even more if prices were lower.