Beware the Fed Overpaying, and Subsidizing Bad Bets

With all the dramatic public health and financial news of the last couple of weeks, thinking about ETF discounts may feel like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. But these discounts provide us with an unprecedented window into financial markets in crisis, and are a natural experiment to test opposing strongly held theories of optimal regulation in a crash.

Exchange-traded funds hold baskets of securities, and I’m going to be looking at bond ETFs, which—of course—hold bonds. Shares of the funds trade on the stock market. Normally the price at which the ETFs trade on the stock market are close to the Net Asset Value of the underlying bonds. For example, if the fund holds $1 billion in bonds, and has 10 million shares outstanding, the shares should trade for about $100 each.

If the ETF price differs significantly from the NAV, certain dealers designated as “authorized participants” can either buy more bonds and put them in the fund in exchange for more shares—which they would do if the ETF traded at a premium to NAV, meaning the ETF shares sell for more than the bonds cost—or redeem ETF shares for the underlying bonds—which they would do if the ETF trades at a discount.

Over the last 12 trading days, we’ve seen ETFs trade at unprecedented levels of discount and—more rarely—premium. This is true for all kinds of ETFs, more for bond ETFs than stock ETFs.

Why does this matter to anyone not trading bonds and ETFs? It’s hard to interpret market prices in a crisis. To what extent do they represent fundamental economic value, versus panicked over-reaction, versus investors desperate for cash. An omniscient regulator would know the fundamental economic value, and slow or close markets when panic took prices too far away from it. This is the theory behind trading halts, circuit breakers, market closures and other mechanisms.

Knowing the fundamental value, this ideal regulator could separate the entities with cash flow issues from the ones that were genuinely insolvent. The former would be supported with liquidity to survive, and the latter would be liquidated promptly to prevent contagion, reduce uncertainty and assure fair resolutions. This is the rationale for rate cuts, liquidity injections and bailouts.

Sadly, we do not have omniscient regulators and we still argue over how much prices in previous crises reflected fundamentals versus panic versus cash needs; and which entities were threatened by illiquidity versus insolvency. This does not stop some people from claiming great certainty about these issues, making strong policy recommendations.

In March 2020 we have two prices, which gives us the potential to measure the effects of panic and cash needs. One theory is that the ETF prices are correct, and that the NAVs are overstated because they are using out-of-date and unrepresentative prices. When news comes out, ETF dealers adjust prices immediately, because there is a lot of trading activity in the ETFs. However, the bond prices used to calculate the NAV won’t start adjusting until—if—people actually trade individual bonds. That doesn’t happen very often, and trade reporting is not instantaneous, it can be delayed minutes, days or forever. Moreover the bonds people trade may not be representative of all bonds, for example people may only offer bonds for sale that have been least affected by the crash.

If that is the “ETF price right” theory, there is also an “ETF price wrong” theory that says ETF prices represent forced selling because this is the only market in which sellers can get liquidity, while NAVs represent arms-length, unforced trades based on fundamental economic value.

People who insist on “ETF price right” argue against providing liquidity to bail out troubled bondholders, because the ETF price shows they are insolvent. People who adhere to “ETF price wrong” support intervention to institutions holding temporarily hard-to-sell bonds.

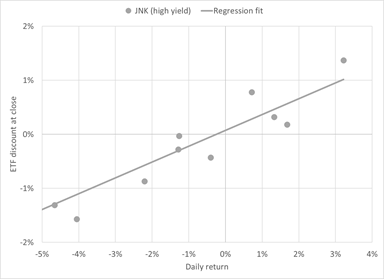

“ETF price right” predicts end-of-day discounts should be proportional to the size of the market move during the day. In particular, it predicts premiums to NAV on days prices increased. This is precisely what we see for the biggest high-yield ETF, as shown below. High-yield, or junk bonds, are bonds from issuers with higher default probabilities than issuers of investment-grade bonds. If the ETF discount represented selling pressure, we would not expect any strong dependence on one day’s performance in one asset class, it should depend on longer-term overall market conditions. The discount or premium should look like random noise, unrelated to the direction of the market on the day.

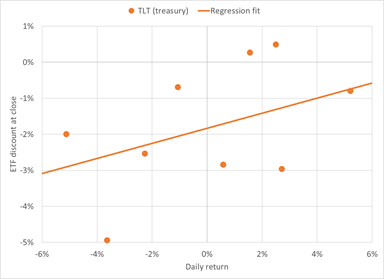

In treasuries, there is less support for “ETF price right.” It’s true discounts are larger on days the market went down, but there are large discounts on average even on days prices went up. The treasury bond prices do seem to lag the ETF, the slope of the regression line is positive, but that does not seem to explain most of the discount.

Investment-grade bonds look like high-yield bonds on days the market goes down. The ETF price looks right. But on days the market goes up, the investment grade ETF trades near market value. This supports the “ETF price right” theory, and suggests the NAVs are reliable as well, but only on days the market goes up.

This suggests the ETF prices are right for corporate bonds. They represent arms-length transactions between unforced participants, while NAVs are unreliable except for investment-grade bonds on days the market is up.

Treasury ETF prices do not seem to be reliable indicators of value. Selling pressure is one explanation for the discounts, but it’s undercut because other securities for liquid treasury trading—the on-the-run bonds—went up in price relative to off the run at the same time the ETFs were going down. So for the moment we leave this unresolved, except to say that people who insist treasury ETF prices are right, or that they’re wrong, have some explaining to do.

The other issue is panic versus rational price changes. “Panic” is shorthand not just for human over-reaction but for institutional constraints, errors, stressed systems or market frictions that cause irrational trades.

If ETF discounts are caused by panic selling then you would expect to make money buying at discounts and selling at premiums. The chart below shows the result of buying the high-yield ETF at end-of-day, for different values of discount. The “ETF wrong” line is what we would expect if the discounts were pure panic. If you buy at a 2% discount, you make an average of 2% the next day.

If the ETF prices were right, and the individual bond prices wrong, we would expect next day return to be uncorrelated to the discount at the previous end-of-day. But we see the slope of the line is even steeper than the ETF-wrong line. This suggests that both ETF and individual bond prices are over-reactions, with ETFs more extreme than individual bonds. If the ETF is trading at a 1% premium, not only do you expect to lose that 1% premium the next day, but you expect the underlying bonds to fall 2% as well for a 3% loss.

In treasuries, the ETF price wrong theory is clearly contradicted. The slope of the regression line is slightly positive, which is the opposite of what we expect if ETF prices represent panic. But it’s close enough to flat to support the claim that the ETF prices are right.

Investment-grade bonds are very hard to explain with either theory. The biggest discount day, -5%, resulted in over +4% return the following day, suggesting the ETF price was wrong. But for all other days, the bigger the discount, the worse the return the next day. This suggests ETF prices are halfway between individual bond prices and the right prices.

Of course, this is only twelve days of data, and perhaps this is an unusual market without broad lessons. But extreme events can generate more useful information that everyday trading and this is the first crisis of this magnitude with established, highly liquid bond ETF trading. No doubt academics will pour over the data using more granular information to tease out nuanced conclusions in a few years.

But for those of us who have to make decisions now, and who trust empirical evidence over opinionated people or untested theories, there are some tentative lessons. Corporate bond ETF prices seem to be correct, with individual bond prices underlying the NAVs often out-of-date. But in the treasury market that does not seem to be the case. In none of the three asset classes does selling pressure explain the ETF price.

For high-yield bonds we have evidence of panicked over-reaction, with the ETF worse than the underlying bonds. But for corporate bonds we have evidence of under-reaction, with the underlying bonds worse than the ETF. Treasury trading has no evidence of either under or over-reaction.

These data give no support to people who want to ignore ETF prices to provide liquidity support or bailouts to institutions that are insolvent if marked to ETF-market. If the central bank buys bonds at bond-market prices, without considering the ETF discount, these data suggest it is overpaying and subsidizing bad bets rather than supplying liquidity temporarily absent from the market.

The data do give support to people who want to slow trading in corporate bond and corporate bond ETF markets with trading halts or curbs, circuit breakers or other devices to let market participants consider decisions carefully, to relieve stress on systems and to give time to adjust institutional constraints and market frictions.

Twelve days of data won’t overturn strongly held convictions, but it’s still worth looking at data when we get it.