How to Revive the American Dream In Blue-Collar America

When it comes to marriage, the nation is increasingly divided. Among college-educated Americans the news about marriage is surprisingly good: divorce is down, nonmarital childbearing is rare, and the vast majority of children are raised in stable, married homes. But for Americans without college degrees, the news is sobering: divorce is high, nonmarital childbearing has never been higher, and about half of children will see their parents' marriage or relationship break down and spend a portion of their lives in a home headed by a single parent.

This growing marriage divide poses obvious problems for children being raised outside of an intact family in poor and working-class communities. It's now well known that children raised in an unstable or single-parent family are much less likely to acquire the human capital, and to avoid detours like a teenage pregnancy or a spell in prison, they need to flourish in today's increasingly competitive marketplace. A recent Brookings study found that 67 percent of adolescents with mothers married throughout their childhood managed to graduate from high school with a GPA of at least 2.5, no criminal record, and no baby as a teen, compared to 42 percent of those whose mothers divorced and just 28 percent of those whose mothers never married. Thus, one big reason that children from poor and working-class homes have more difficulty realizing the American Dream today is that they are much less likely to have had the benefit of being raised in a stable home with two parents devoting time, attention, and money to their future.

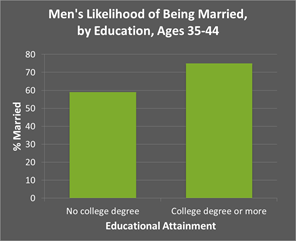

College-educated Men Are More Likely to Be Married

Source: Current Population Survey, 2013

But another, largely unheralded problem with the marriage divide is that it has left millions of men in poor and working-class communities disconnected from the routines, responsibilities, and rewards of ordinary family life. The marriage divide means that only 59 percent of 35-44-year-old men without college degrees are married, compared to 75 percent of men with college degrees, according to the 2013 Current Population Survey. That's important because, as Nobel Laureate George Akerlof has observed, marriage tends to make men work harder, more strategically, and make more money.

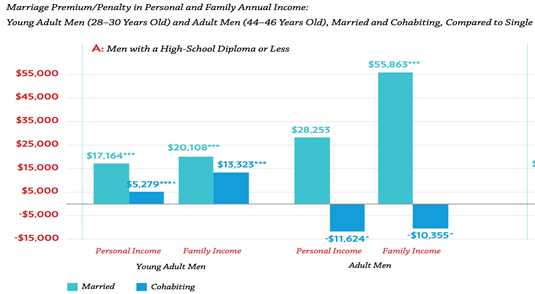

Men's Marriage Premium

Source: Lerman and Wilcox, 2014.

The figure above, derived from a recent American Enterprise Institute-Institute for Family Studies study we coauthored, is indicative of the power that marriage has in men's lives. It shows that even non-college educated men still benefit from marriage: because they work significantly more hours than their single peers, such men make at least $17,000 more per year if they are married compared to their single peers. This same study finds that 37 percent of the decline in men's employment since the 1970s can be linked to declining marriage rates. Indeed, as the figure below shows, men who are not married with children make up a disproportionate share of men who are not employed today. The fact, then, that fewer men in working-class and poor men are getting and staying married, then, helps to account for why all too many of them are falling behind in our society.

In the face of this growing marriage divide, the responses on both sides of the ideological spectrum are insufficient. Some on the left suggest that we accept these new realities and respond by expanding the safety net to make up for the fallout of the "new normal" for low- and increasingly middle-income families. But our historical approach of offering income support to single mothers and children, while offering very little support to the fathers, has clearly not "solved" the problem of poverty, and has done nothing to engage lower-income men. Meanwhile, some observers on the political right blame these changes on an erosion of values and call simply for new cultural messages. But such calls ignore the new economic realities that make marriage much more difficult for Americans without college degrees than for those with a college diploma.

To bridge the marriage divide, the nation needs a bipartisan commitment that attends to the economic, policy, and cultural roots of this divide. Four approaches-two drawn from President Obama's budget proposal, and two drawn from Republicans on the Hill-would strengthen the economic and cultural foundations of marriage and family life among poor and working-class Americans. First, the president's proposal to push for a major infrastructure campaign will bring needed improvements to the nation's roads, bridges, railroads, and airports; a side benefit is that it will also provide jobs to many Americans left out of the recovery. Second, to improve the marital prospects of young adults from low-income communities, we need to address the weak economic prospects of non-college educated men. Here, the president has proposed expanding vocational and apprenticeship programs that connect young adults to good jobs with good wages, as well as expanding the EITC for single adults. These measures would incentivize work and bolster the economic position of single men.

Republicans in Congress are also advancing ideas that would strengthen marriage and family life. One is the Lee-Rubio tax plan that would more than triple the child tax credit to $3500 and extend it not only to income taxes but also to payroll taxes, thereby strengthening the economic foundations of millions of blue-collar and middle-class families across the nation. Senator Scott has also talked about finding ways to reduce some of the marriage penalties now facing lower-income couples, including lower-income couples with two earners in the labor force; this bill would also help to launch a public education campaign touting the benefits of forging a healthy marriage, especially before couples have kids. Cultural messages and media matter, and we should use them to promote socially responsible outcomes.

Efforts like these may seem quixiotic: How can public policy tackle a problem as complex as marriage, an issue bound up with questions of sex, childbearing, and morality? Not long ago, however, teen pregnancy seemed equally intractable. But in the mid-1990s, there was a national recognition that this was a social problem and there was a commitment to bringing down teen childbearing rates with a range of private and public initiatives. A remarkable thing happened: teen childbearing has fallen by more than 50 percent since the early 1990's. It is time for the country to unite around a similar effort to bridge the marriage divide in America. We need to come together to support a new era of stable marital unions that are consistent with contemporary commitments to shared respect and responsibilities between spouses and that provide for stable, nurturing home environments for our children. That's because the present state of our unions-in which too many children lack a stable, two-parent home, and too many men and women lack the durable connections and economic support of family life-is opening up an unacceptable social and economic divide between the college educated and the less-educated that is unacceptable to all of us who believe that the American Dream should be accessible to all.